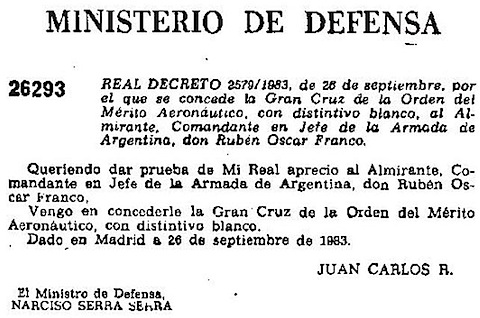

A Spanish royal decree ordering the awarding of a military medal to Argentine admiral Rubén Oscar Franco. As you can see, it bears the names of King Juan Carlos and the then defence minister, Narciso Serra. “Wishing to give proof of My Royal appreciation to Admiral, Commander in Chief of the Navy of Argentina, don Rubén Oscar Franco, I come to concede the Great Cross of Aeronautical Merit with white distinction…” This decoration came years after the re-democratization of Spain, following the death of another notorious military chief, also named Franco. Perhaps you’ve heard of him? He used to be known as the Generalissimo. And his régime was no less bloody and cruel than that of Argentina, and no less given to “disappearing” leftists and dissidents and other so-called undesirables. The terror and the forgettance went on in Spain for four decades, and doubts continue to this day as to how democratic it really is in sunny España. So perhaps it’s no wonder that even after Spain reverted to democratic government, the Franco-installed royal family of Borbón was happy to co-operate in whitewashing Argentina’s reign of terror, no matter which party ran the government…

If ever there is a ranking of torturers, the members of the Argentine navy will hold a place of distinction. Between 1976 and 1983, their torturers subjected thousands to abuses as horrible as they are insupportable. For Rubén Oscar Franco, chief of the navy in the last years of the military dictatorship, those gravest violations of human rights were part of a “war against an aggression which came from outside”. So he said in June of 1983, during an official visit to Ecuador. Far from being rejected by the international community, the military officer won a prize: on September 26 of that same year, the Spanish government awarded him the “Great Cross of the Order of Aeronautical Merit”.

Ex-admiral Franco is 87 years old now. Last May, a tribunal sentenced him to 25 years in jail for his participation in the kidnapping and appropriation of children of the disappeared. Among other things, the judiciary determined that this military man ordered the burning of documents that contained information over cases of stolen children. Before that, this sinister sailor had been involved in the trafficking of weapons to Croatia during the Balkan war, one of the episodes of corruption that marked the reign of Carlos Menem (1989-1999). His name also figured in the extradition request formulated in 1999 by [Spanish judge] Baltasar Garzón, who was then investigating the crimes of the Argentine dictatorship. According to the judge, Rubén Franco had held responsibilities in the plan of annihilation which left a toll of 30,000 disappeared persons.

In the fall of 1983, his name had already appeared in international denunciations against the military junta. Those same denunciations also arrived at the offices of the PSOE [Socialist party] of Spain, which before that summer had demonstrated against the self-amnesty which the Argentine military rulers granted themselves before abandoning power. In spite of that, the Spanish defence minister, Narciso Serra, had no difficulty in signing off on the award for the Argentine Franco. Like all the other awards revealed this week by Público, the decree in question also bore the signature of King Juan Carlos.

A few days before, the Spanish monarchy and the González government had awarded the Great Cross of the Order of Naval Merit with White Distinction to Argentine rear-admiral Ciro García, who was chosen by General Videla in 1978 to defend his interests before the Inter-Governmental Maritime Consultive Organization in Europe. According to determined information, this military officer had been linked to intelligence tasks.

According to Público, naval officers Franco and García were not the only Argentines decorated by the PSOE executive. On June 8, 1984, the Spanish state awarded an “Order of Military Merit with White Distinction” to Juan Manuel Tito, former chief of the military in the government of Raúl Alfonsín. In spite of his new democratic role, Tito had made a career in Videla’s army, becoming chief of the Regiment of Grenadiers.

In any case, relations between the government of Felipe González and the Argentine dictatorship did not end there. As well as awarding these decorations, the Moncloa Palace also permitted that Spanish military officers could continue to take courses in Argentine institutions, a practice which had been begun by the previous Spanish government, under Adolfo Suárez. As may be seen in the lists which the Spanish ministry of defence still keeps, in 1983 Lieutenant-Colonel Julián Soutullo Pérez was sent to the Argentine army intelligence school to take one of the courses they offered to foreigners.

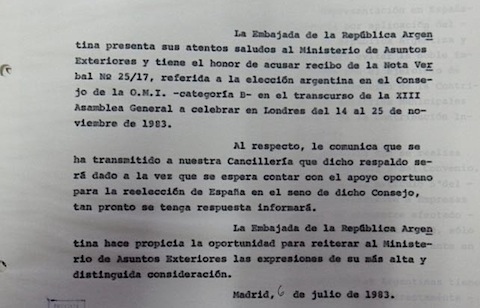

During that same year, Spain and Argentina also maintained a fluid exchange of official support in international organizations. Just as what took place during the Suárez administration, Madrid and Buenos Aires had a practice of “I’ll vote for you if you vote for me”. In this sense, certain documents Público accessed reveal that the PSOE government sought the support of the dictatorship in organizations such as the International Meteorological Organization, and the International Maritime Organization. If Argentina voted for Spanish candidates, the executive of the González government promised to value this gesture “to a high degree”.

According to other secret archives, the Spanish state also tried to obtain Argentine support to become the headquarters of the International Centre for Genetic and Biotechnological Engineering. For its part, the military junta showed its decided support to the Spanish candidacy in the International Civil Aviation Organization. In return, representatives of that country had to vote for Argentine postulants. These were always in the hands of the same protagonists: the Spanish ministry of Exterior Affairs, and the diplomatic corps of the dictatorship, which dedicated itself to bringing the requests before their chiefs in Buenos Aires. Many of them are in jail today.

Translation mine.

Here’s another document showing the chummy rapport between Spain and Argentina, even during a time when the junta’s tortures and disappearances had become common knowledge around the world:

“The Embassy of the Republic of Argentina presents its attentive greetings to the Ministry of Exterior Affairs and has the honor of acknowledging receipt of Verbal Note No. 25/17, referring to the election of Argentina to the Council of the O.M.I. [International Meteorological Organization], category B, during the 13th General Assembly in London, November 14-35, 1983. With respect [to that], the communiqué our Foreign Ministry has transmitted, which states support will be given at any time when one expects to count on opportune support for the re-election of Spain to said Council, as soon as there is an answer, we will inform. The Embassy of the Republic of Argentina will make propitious the opportunity to reiterate to the Ministry of Exterior Affairs the expressions of its highest and most distinguished consideration.”

Well. That’s a lot of flowery diplomatese, but there you go. “Democratic” post-Franco Spain, meet not-so-democratic Franco of Argentina.

As for the rest of the world, well…don’t hold your breath waiting for them to explain this. El Twit de Borbón is silent as the grave on this, even though he was there for all the investitures in question.